Biking Provides a Critical Lifeline During the Coronavirus Crisis

As the world works to stop the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, more than3.9 billion peopleare under full or partial lockdown orders, as of mid-April. Citieshave curtailedmany public transit operations because of declining ridership and health concerns. While these measures are essential for preventing the spread of the disease, they present challenges for the many people who still need to get around cities for essential tasks like buying food or caring for a loved one. And mobility for essential workers like health care providers is more important than ever.

Some evidence suggests many people are turning to cycling as a resilient and reliable option to fill the gap. Many urban cycling networks have seen a surge in traffic, including in China,Germany,Ireland, theUnited Kingdomand the United States. InPhiladelphia, cycling has increased by more than 150% during the COVID-19 outbreak. Some governments are responding to the spike in demand by opening emergency bike lanes and giving essential workerspersonal access to their own bikesfrom shared fleets.

At a time when city leaders are rethinking many past assumptions, this trend is a unique opportunity to embrace cycling as an integral part of urban transport systems — not just as an accessory. Cities need more resilient, more equitable mobility — not only to weather the current storm, but to prepare for future crises.

Amidst COVID-19 Lockdowns, Cycling Emerges as a Resilient Way to Stay Connected

Throughout the two-month lockdown of Wuhan, China, ground zero of the COVID-19 outbreak, volunteers used bicycles to deliver necessities to residents stuck at home. Some bikeshare companiesamped up sanitizing effortsandmade their services free of chargeto allow access to medical workers and those with urgent needs.

From January 23 to March 12, Meituan Bikeshare, formerly known as Mobike, provided about 2.3 million trips in Wuhan,according to its own data collection, accounting for more than half of all non-walking trips in the city during the epidemic. A total of 286,000 people used the service, with a total cycling distance of more than 2 million miles, equivalent to 81 laps around the equator. Meanwhile, the average daily distance for a single ride increased 10%, showing an increased reliance on bicycles for longer trips.

Similar trends are evident in other cities around the world. New York City’s public bikeshare system, Citi Bike, saw a67% surge in demandin early March compared with the same period last year.ChicagoandPhiladelphiasaw ridership in their bikeshare programs nearly double during March. One of Philadelphia’s major bike trails experienced a470% increase in traffic. London issuedspecial guidance for new ridersand, before lockdowns shut down all non-essential shops and traffic,bike shops in Dublinwere seeing more business than ever.

New Infrastructure to Support Increased Cycling

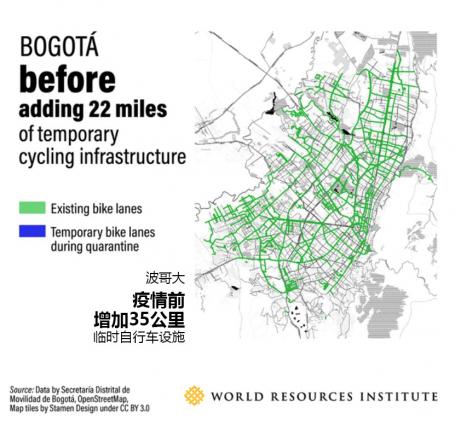

Some cities are temporarily or permanently expanding cycling infrastructure in response to COVID-19. Bogotá experimented withopening up its 22-mile Ciclovía network, a system of streets normally closed to cars on Sundays, during other days of the week. In a pilot project conducted withNUMO, the New Urban Mobility alliance, the city and a private bike operator are alsolending e-bikes to health care workers.

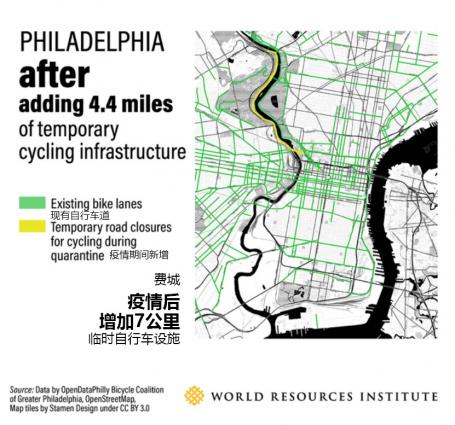

Philadelphia responded to a public petition to create more space for cyclists and pedestrians to operate safely byclosing a large 4.4-mile road segmentto motor vehicles. Mexico City proposedplans for 80 miles of temporary bike infrastructureto alleviate the risks of public transportation use and facilitate mobility in the megalopolis of more than 21 million people. Berlin recently implemented a 1-miletemporary bike lanealong a major road and has plans to expand the pop-up infrastructure, along with133 other German cities.Oakland,Minneapolis,Denver,Louisville,&VancouverandCalgaryhave implemented similar measures. New York City committed toadding close to 1 mile of temporary protected bike lanesto segments of Manhattan and Brooklyn, and testingroad closures to cars.

Building Back Better

Cycling is providing a critical lifeline to many cities during a critical time. But it’s also a resilient mode of transport that can continue to provide valuable benefits to cities in the future, too — benefits that go beyond mobility.

1. Better bike accessibility can support economic recovery after COVID-19

The global economic impact of the coronavirus crisis is already severe and expected to worsen. Many governments are contemplating massive infrastructure projects that can generate jobs and economic activity. There is a strong case — for the environment, public health and the economy — to avoid projects and infrastructure that cause more burning of fossil fuels. Investing in infrastructure to support biking — from protected lanes, to mass parking facilities to bikeshare programs — is exactly the type ofwin-win investmentthat will help economies recover while curbing climate change, reducing air pollution and protecting human health.

Each kilometer cycledavoids 250 grams of CO2 emissions, making bicycles a key option for low-carbon transport. Copenhagen’s cyclists are collectively estimated to avoid20,000 tonsof carbon emissions annually, the equivalent of50 million milesdriven by private passenger vehicles.

As social distancing eases and people can return to patronizing local shops, cafes and restaurants in-person, bicycle use can also provideproven stimulus to economic activityon main streets and commercial areas. Studies have shown that cyclistsspend on average 3 times more than car driverswith local businesses, and that cycling infrastructure iscorrelated with higher retail sales.

2. Biking can improve public health and quality of life

Cycling positively impacts everyone’s health by improving urban air quality. Regular cyclists enjoy the benefits of consistent exercise; they have a40% lower chance of getting cancer, are 40% less likely to die prematurely and are more than 50% less likely to have heart disease. One study has shown a15% increased risk of fatality from COVID-19in areas with higher levels of air pollution, likely due to poorer lung health. Cycling offers a way to reduce local air pollution and increase physical activity, which improves individual resilience.

3. Biking infrastructure can help cities become more resilient to future shocks

Bicycle access is already proving key to people operating under constrained economic and transportation conditions. The increased mobility offered by cycling during power outages, natural disasters or other disruptions to urban transport systems is significant, providing aservice area that can be 15 times larger than walking alone.

Embracing Cycling as a Response to Crises

The Netherlands is one of the world’s most successful cycling nations. The country is home to more than 23,000 miles of protected bike lanes, and more bicycles than people. A quarter of all trips are made by bicycle. The Netherlands is also one of the safest countries to be a biker, with an annual cyclist fatality rate of just1.1 per 100 million kilometers cycled(compared to 5.8 in the United States).

This status was never a given. Change sprang in response to a road safety crisis, particularly among children, and the OPEC oil embargo in the 1970s. The government announced car-free Sundays in 1973, and the country slowly began to reevaluate its relationship with cars.

In a more recent case, cycling proved to be a resilient and reliable mode of transportation during the2017 earthquake in Mexico City. After the devastation of thousands of buildings left many roads inaccessible to motor vehicles, the city depended heavily on personal bikes and its bikeshare system for first responders and volunteers bringing first aid and supplies.

COVID-19 is another crisis that challenges cities everywhere to think about how urban transport networks might operate differently. It’s a time for cities to experiment, using their streets as testing grounds for change. For instance, WRI Ross Center is working with NUMO andPopulus, a company that provides mobility data and tools to cities, tomeasure improved accessto job opportunities and essential services like hospitals and grocery stores with newly expanded networks of temporary bike lanes.

Today’s COVID-19 lockdowns could reveal solutions that have far-reaching benefits for cities long into the future, pointing the way to more resilient, accessible and safe urban transport. A city with more cycling is a city with healthier people, safer streets, cleaner air and better connectivity.